Content warning: Brief description of having a seizure.

On Memorial Day 2005 I sat on an ugly floral couch in my parents’ basement. I held a tiny Tegretol pill in my hand—what I hoped would be my last anti-seizure medication dose—and thought back over the last 5 years.

In June of 2000 I had been sitting on that same couch. I was 10, watching Mrs. Doubtfire with my best friend and parents. Halfway through the movie the left half of my face went numb. My first thought, “Did I go to the dentist today?” I hadn’t. I brought my hand to my face. My hand felt my cheek, but my cheek didn’t feel my hand. The other side felt normal. I reached for my Diet Coke Caffeine Free (ew, why), hoping that a sip would bring the feeling back to my face. It somehow made things worse.

I stood up hoping for a restart, but I only became more confused. All I could say was, “Mom? Dad?” before my mouth and body stopped obeying any of my commands. My hands went to my chest and the room blurred. My parents and friend felt far away. For a moment they all kept looking at the screen, probably thinking I was going to the bathroom. My Mom noticed me first, then I was laying on the couch, and that’s the last thing I remember.

I came back to consciousness with my best friend weeping, my mom praying/crying, and my dad frantically on the phone in the other room. Something bad had happened. In my 10 year old brain, I thought if we just kept watching Mrs. Doubtfire we could pretend everything was okay. “I just ate too many Nerds.” Just as I was asking to continue the movie, I heard the sirens in the background getting closer to our house.

Back on that floral couch in 2005, my 15 year old self was ready to leave the confusion and fear behind. I popped some peanut M&Ms in my mouth and swallowed them with that last Tegretol pill. I sat there for a few minutes and reflected on the chapter of my life I was closing. I got up, planning on leaving the neurologists, MRIs, EEGs, sleep tracking, flashbulb memories, and medication alarm clocks behind. I left out the basement door and went to play with a friend.

In How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom, Johanna Hedva shares about their 9 year-old self’s perspective on life amidst internal and external anguish: “Life made me feel the question ‘why me?’ in equal extremes. That my life was extraordinary, a miracle of random chance and luck, and that it was the most elemental burden. To be thrown here, without choice.”

To be thrown here, without choice.

Soon after my seizure I said, “I wish I was never born” to my mom. I wasn’t necessarily wanting to die, I was communicating something I didn’t have words for. I was reckoning with a life and body I hadn’t asked for. It confused me that I used to not exist, and then all of the sudden I did, and 10 years later I had to worry about my brain waves freaking out and making me lose control of my body. I worried and then worried about that worry because the worry was making me not be able to sleep—a risk factor for seizures. Things snowballed, all focused on my rebelling body.

At the same time, I got my first Razor scooter that summer and loved the freedom it gave me. I could eat Jelly Belly’s, drink Pepsi, and innertube. I could swim—but I’d constantly imagine having a seizure and being trapped in my sinking body. I could play with friends—but I’d call my parents the moment I “felt weird” or felt a slight twitch in my face.

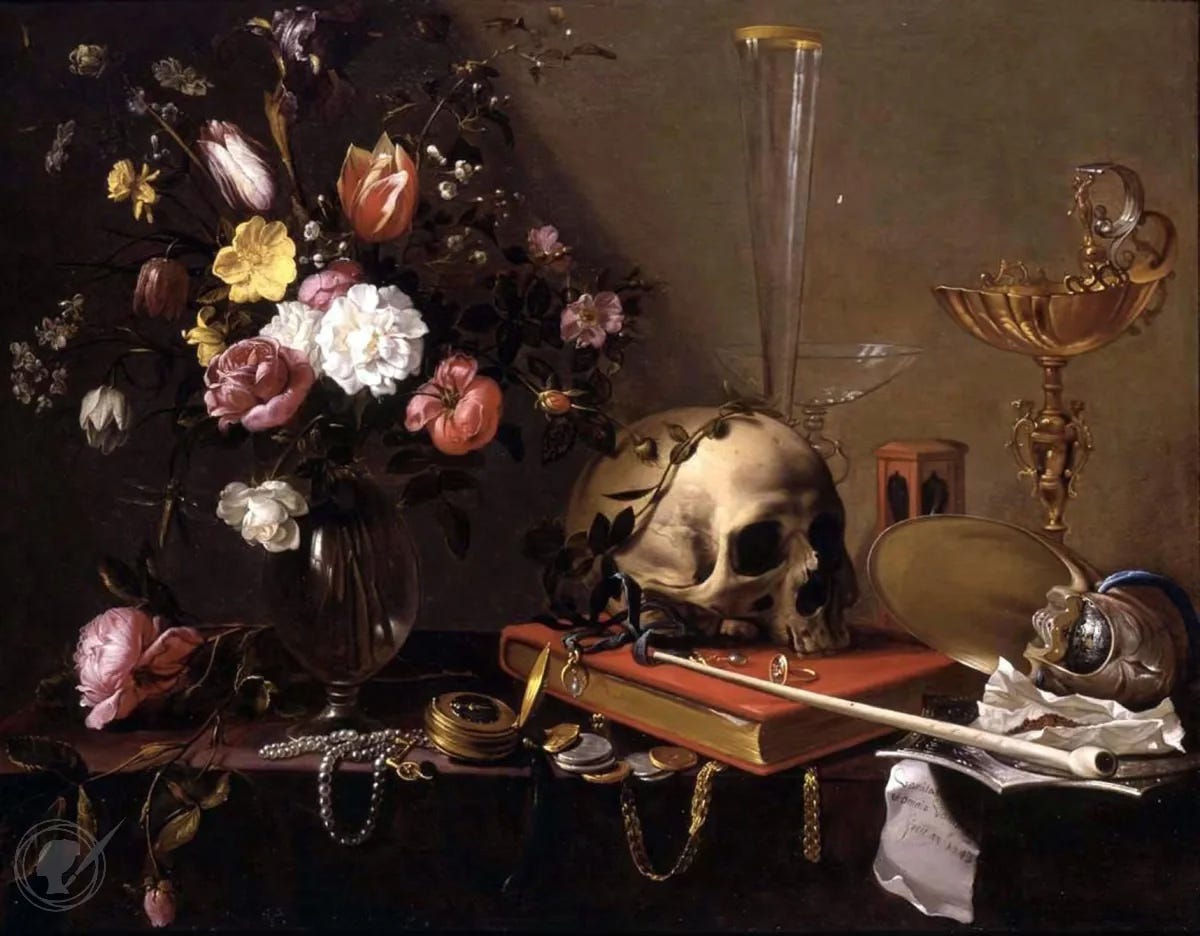

These memories make me think of the lifelong joys and terrors of having a body, and how they often mix together. We’re thrown here without choice, and the rest is a mixed bag. Not only are we thrown here as a consciousness, but we’re thrown here in a body. A physical, ever-changing, very high maintenance body.

Johanna Hedva considers this reality: “That the body gets depleted simply by doing what it is meant to do. That pain rushes into your joints after moving, that your teeth get chipped from chewing, that seeing and looking and watching weakens your eyes.” Hedva concludes: “Sometimes I think that the history of the world is the history of trying to cope with this thing called the body.”

Having a body—or being human—often feels like a push-pull between our transcendent consciousness and our mundane bodies. Existentialist Ernest Becker said it crudely: “Humans are gods with anuses.” We are gods—we hold the divine potential to experience beauty and connection. We make meaning out of everything. We think about eternity. We think about the past and future of our non-existence. We also reckon with our base needs. Our very needy bodies that require our thought, time, energy, and money just to keep existing. Our teeth chip, we get chronic illness, our bodies change—in Becker’s words, we have anuses (the last time I’ll write that word here, I promise).

In theory, gods live solely in their infinite potential. They live forever with no physical body to hold them back or remind them of time and decay. They live in eternity and will be for eternity. Alternatively, animals live in the moment in response to instincts. Eat, sleep, find shelter, reproduce, run from predators. They’re unable to ponder their eventual non-existence. They’re just existing. Now, now, now, now, dead.

Humans have a foot in both planes of existence. Like gods, we think about eternity and meaning. We want—at least part of us—to exist for eternity. But like animals, we have these bodies that need constant care and attention. Our bodies will die. We’re stuck in the middle; we know that eternity exists but we also know our bodies are on a timeline.

Our consciousness and existence depend on these fickle, fragile bodies. When these bodies are done, poof. These bodies that can be so capable of rest, pleasure, connection, and meaning will also be the cause of our end. Our bodies are constant reminders that some day we will no longer exist. Our bodies are both giver and taker of our lives. Fun.

I wonder if this contributes to the complicated relationship many of us have with our bodies. Deep down, we know these bodies will be the reason our consciousness no longer exists. (If you believe in the afterlife, our bodies will at least be the end of everything we know on this earth.) It’s freaky, our bodies will kill us.

It’s entirely understandable that we’d much rather focus on the minutia of having a body—creating hierarchies of “good” to “bad” bodies, monitoring wrinkles and diet, counting steps, reversing aging, comparing our bodies to past versions of ourselves and others, trying to—or wishing we could—move our bodies closer to the top of bodily hierarchies. These aspects of our bodies can give us a semblance of control and they can distract us from a much more disturbing reality. But they also hold us back from the fullness of having a body for the little time we’re here.

Up until my seizure, I had every reason to believe my body would always be under my control. I lived in a context that valued physical achievement, and I excelled at it. Being a white non-disabled boy, I existed at the top of most bodily hierarchies. My seizure created a fault in my imagined superiority and security in my body. I’m pretty staunchly opposed to demanding meaning and positive outcomes from life’s challenges, but I do know that the seizure forced me to reckon with the reality of my body in a way that I otherwise wouldn’t have.

But my 10 year old mind wasn’t ready. Maybe we’re never ready for that.

Last weekend I found myself back on that ugly floral couch. Alas, my hope to leave all that body trauma behind on that Memorial Day weekend was a bust. Back then, my goal really was to leave it all behind, to pretend that the seizure—and by extension my inability to make sense of this body and life—didn’t exist. Wouldn’t that be nice.

This time on that floral couch—25 years after the seizure—I kept trying to find a sense of okayness amidst my ever-changing and ever-needing body. At this point, my returning to that couch is a compulsive search for peace in a body and world that can feel sort of terrifying. Coming back to that couch represents my decades-long attempt to find an ever-cozy and ever-easy home in my body. But man, I don’t think that exists.

Next time I find myself on that couch, I hope it’s a time to sit amidst the weeds of being human. Avoiding the weeds—or trying to disappear them—leads to an unintentional disappearing of the exhilarating, connected aspects of being human. I want to come home to the weedy, uneasy but pretty magical experience of being a body-mind. I think the weeds will complement the couch’s floral print well.

The specifics here - the floral couch, the nerds, Mrs. Doubtfire - they’re a time capsule of this seminal moment in your life. I wonder what specifics you’ll bring to the floral couch next, what the time capsule of weeds will look like now and 10 years from now. Octavia Butler says that change is the only constant. All that you touch you change, all that you change changes you.

I really resonated with the subject. I think we often think we have control over our bodies especially when we are healthy. So well said, Kent.